That is, if thread 1 produces a variable value that will be used by thread 2 (as in the average example in the IntroThreads lecture), thread 1 performs the computation, stores the value, and spawns the threads that then use this computation.

This form of parallelism is often called "producer-consumer" parallelism and it occurs in operating systems frequently. In this example, thread 1 "produces" a value that thread 2 consumes (presumably to compute something else).

Perhaps more germane to the class at hand, this problem is also called the bounded buffer problem since the buffer used to speed-match the producers and consumers has a fixed length. In an operating systems context, these types of synchronization problems occur frequently. There are cases where threads and/or devices need to communicate, their speeds differ or vary, and the OS must allocate a fixed memory footprint to enable efficient producer-consumer parallelism.

While it is logically possible to spawn a new thread that runs every time a new value is produced and to have that thread terminate after it has consumed the value, the overhead of all of the create and join calls would be large. Instead, pthreads includes a way for one thread to wait for a signal from another before proceeding. It is called a condition variable and it is used to implement producer-consumer style parallelism without the constant need to spawn and join threads.

Condition variables are a feature of a syncronization primitive called a monitor which is similar to the way in which operating systems kernels work. We won't discuss them formally at this juncture but their use will become clear as the class progresses. For pthreads, however, condition variables are used to

Thus clients

and traders

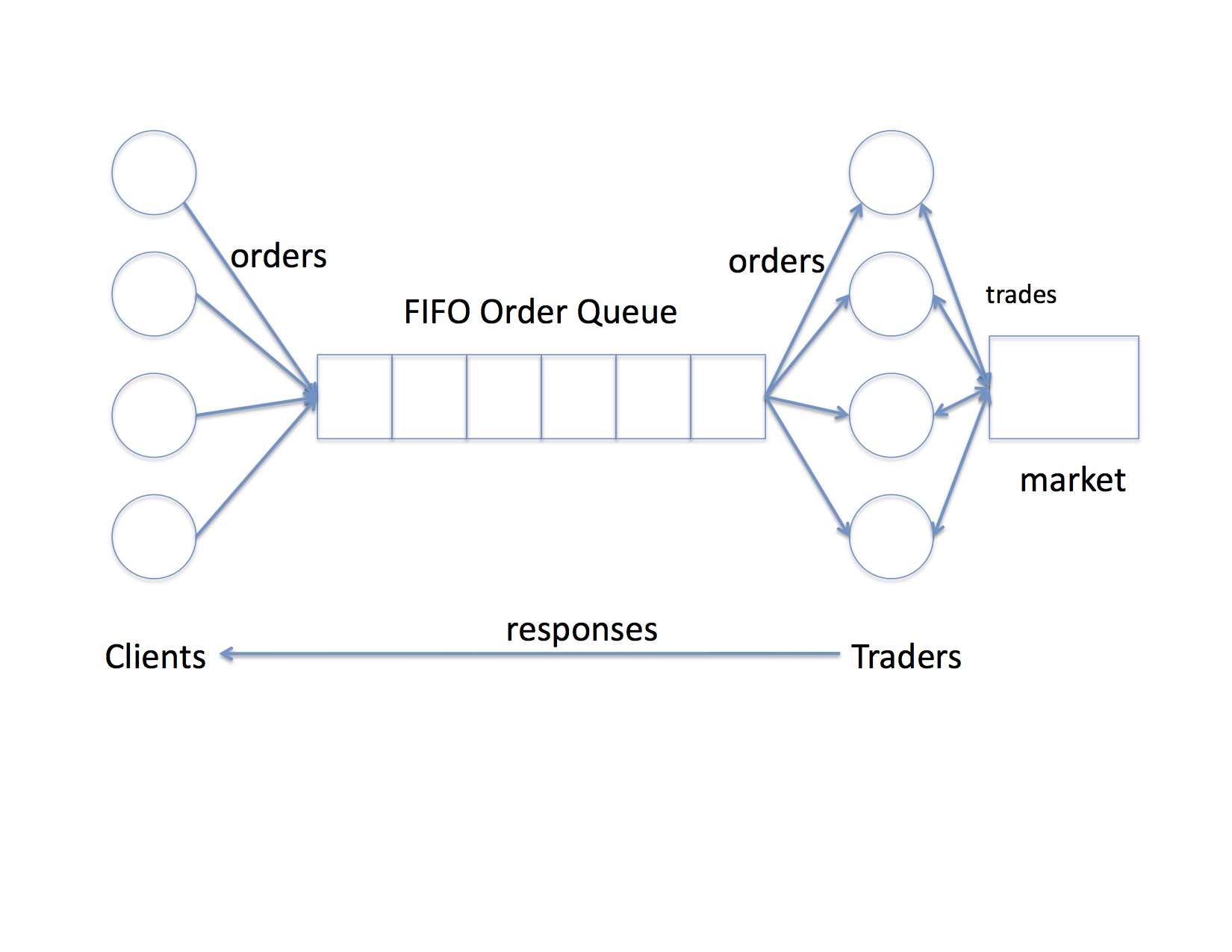

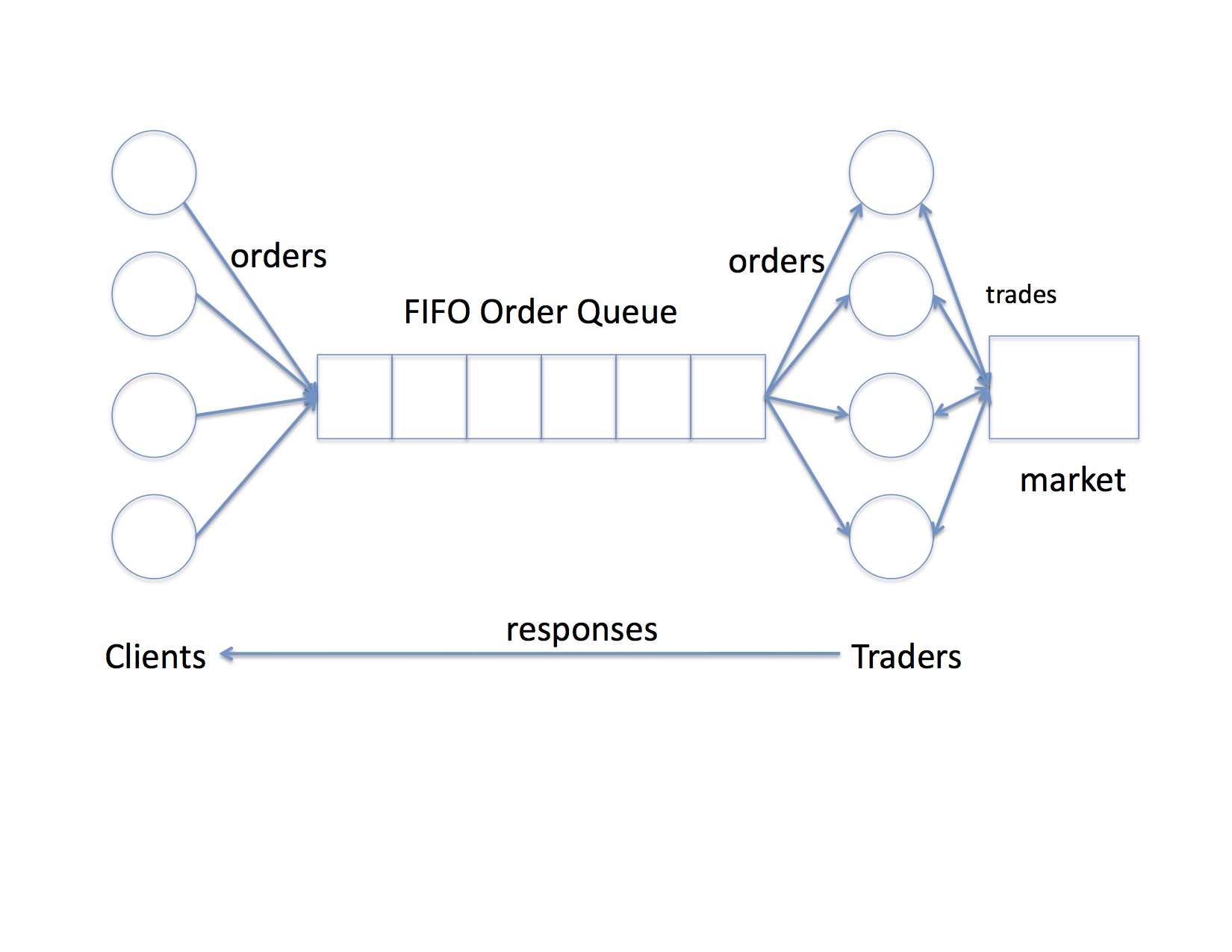

First, let's start with a picture. Often the easiest way to begin to understand these types of syncronization problems is with a picture.

This will be a simplified example that we'll implement using pthreads. In it, clients use the queue to send their orders to traders, and the traders interact via a single shared "market" and then send responses directly back to clients.

There four main data structures:

Here are the C structure definitions for these data structures:

struct order

{

int stock_id;

int quantity;

int action; /* buy or sell */

int fulfilled;

};

struct order_que

{

struct order **orders;

int size;

int head;

int tail;

int size;

pthread_mutex_t lock;

};

struct market

{

pthread_mutex_t lock;

int *stocks;

int count;

};

Notice that the struct market structure just uses an array of integers

to represent the array of possible stocks. Each stock is named by an integer

that is passed from client to trader in the int stock_id field of the

order.

The struct order_que has a pointer to an array of pointers to orders, a head and tail pointer to use for the FIFO, and a size indicating how many elements there are in the array of pointers to orders. Thus each element in the queue points to an order that has been dynamically allocated. The size of that queue of pointers is also used to dynamically allocate the array itself. To see how this works, it is helpful to study the constructor function for a struct order_que

struct order_que *InitOrderQue(int size)

{

struct order_que *oq;

oq = (struct order_que *)malloc(sizeof(struct order_que));

if(oq == NULL) {

return(NULL);

}

memset(oq,0,sizeof(struct order_que));

oq->size = size;

oq->orders = (struct order **)malloc(oq->size*sizeof(struct order *));

if(oq->orders == NULL) {

free(oq);

return(NULL);

}

memset(oq->orders,0,size*sizeof(struct order *));

oq->count = 0;

pthread_mutex_init(&oq->lock,NULL);

return(oq);

}

Notice that the size parameter is used to malloc() an array of

pointers to struct order data types. If you don't understand this use

of malloc() and pointers, stop here and review. It will be important

since dynamic memory allocation, arrays, structures, and pointers are

essential to success in this class.

Clients create a struct order data type, fill it it with their randomly generated order information, and queue it on an order queue (of which there will only be one in these examples). Then the client waits for the int fulfilled flag to indicate that the order has been fulfilled by a trader (which will set the flag to 1).

The client has to retain a pointer to the order so that it can "see" when the order has been fulfilled, deallocate the order, and loop around to create a new one.

./market1 -c 10 -t 10 -s 100 -q 5 -o 1000says to runs the simulation with 10 clients, 10 traders, 100 stocks, a queue size of 5, and each client will issues and wait for 1000 orders to complete.

Without the -V each simulation prints out the transaction rate. That is, the number of orders/second the entire simulation was able to achieve using the parameters specified.

For these reasons, operating systems often implement queues (like the one in the simulation) using an array. For an append operation, data is enqueued at the head (or the tail) of the array and removed at the tail (or the head). If you are super worried about performance, you can use the difference between the head and tail pointers as a measure of in-use capacity (with an extra slot to differentiate full from empty conditions). However, for clarity (and because the performance difference is probably immeasurable on a single machine) the code uses an "extra" count field to track the number of entries in queue. I think it is easier to understand even though there is an extra increment and decrement inside each critical section.

All of the examples and a makefile are available from http://www.cs.ucsb.edu/~rich/class/cs170/notes/CondVar/example

First look at the arguments passed to the client thread:

struct client_arg

{

int id;

int order_count;

struct order_que *order_que;

int max_stock_id;

int max_quantity;

int verbose;

};

The clients need to know the address of the order queue (struct order_que

*)), how many orders to place (int order count),

the maximum ID to use when choosing a stock (int max_stock_id), the

maximum quantity to use when choosing a quantity (max_quantity), an id

for printing, and the verbose flag.

Note that the pointer to the order queue will be the same for all clients so that they share the same queue.

Next look at the body of the client thread code:

void *ClientThread(void *arg)

{

struct client_arg *ca = (struct client_arg *)arg;

int i;

int next;

struct order *order;

int stock_id;

int quantity;

int action;

int queued;

double now;

for(i=0; i < ca->order_count; i++) {

/*

* create an order for a random stock

*/

stock_id = (int)(RAND() * ca->max_stock_id);

quantity = (int)(RAND() * ca->max_quantity);

if(RAND() > 0.5) {

action = 0; /* 0 => buy */

} else {

action = 1; /* 1 => sell */

}

order = InitOrder(stock_id,quantity,action);

if(order == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr,"no space for order\n");

exit(1);

}

/*

* queue it for the traders

*/

queued = 0;

while(queued == 0) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&(ca->order_que->lock));

/*

* is the queue full?

*/

if(ca->order_que->count == ca->order_que->size) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ca->order_que->lock));

continue;

}

/*

* there is space in the queue, add the order and bump

* the head

*/

if(ca->verbose == 1) {

now = CTimer();

printf("%10.0f client %d: ",now,ca->id);

printf("queued stock %d, for %d, %s\n",

order->stock_id,

order->quantity,

(order->action ? "SELL" : "BUY"));

}

next = (ca->order_que->head + 1) % ca->order_que->size;

ca->order_que->orders[next] = order;

ca->order_que->head = next;

ca->order_que->count += 1;

queued = 1;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ca->order_que->lock));

/*

* spin waiting until the order is fulfilled

*/

while(order->fulfilled == 0);

/*

* done, free the order and repeat

*/

FreeOrder(order);

}

}

return(NULL);

}

In this code segment the lines where the client is synchronizing are in bold

face. Notice that the head and tail pointers for the share order queue must

be managed as a critical section. Each client must add an order and update

the head and tail pointers atomically.

To do this using pthread_mutex_t is a little tricky. Why? Because the client must test to make sure the queue isn't full before it updates the head and tail pointers (or an order will be lost). If the queue is full, the client must wait, but it can't stop and wait holding the lock or a deadlock will occur. Thus, when the queue is full, the client must drop its lock (so that a trader can get into the critical section to dequeue an order thereby opening a slot) and loop back around to try again.

This type of syncronization is called "polling" since the client "polls" the full condition and loops while the condition polls as true.

Notice also that the client comes out of the polling loop holding the lock so that it adds the order to the queue and moves the head pointer atomically. Only after it has successfully added the order to the queue does the client drop its lock.

The other tricky business here is in the code where the client waits for the trader to fulfill the order

/*

* spin waiting until the order is fulfilled

*/

while(order->fulfilled == 0);

Why is there no lock? Notice that the lock for the order has been dropped.

Should there be a lock here?

Well, if there is, it can't be the same lock as the one for the order queue or the trader (which will also use this lock to test the empty condition) won't be able to get into the critical section to dequeue an order. It is possible to have added a pthread_mutex_t lock to the order structure but the syncronization of the fulfillment of a single order is between a single client and a single trader. That is, the client and trader are not racing. Rather, the trader needs to send a signal to the client that the trade is done and the client needs to wait for that signal. Since there is only going to be one client waiting and one trader sending the signal, the client can simply "spin" polling the value of the int fulfilled flag until the trader sets it to 1. This method of syncronization works only if the memory system of the processor guarantees that memory reads and writes are atomic (which the x86 architecture does).

Thus the while loop shown above simply spins until the value in the order structure gets set to 1, thereby "holding" the client until the trade completes.

The trader thread code is as follows:

void *TraderThread(void *arg)

{

struct trader_arg *ta = (struct trader_arg *)arg;

int dequeued;

struct order *order;

int tail;

double now;

int next;

while(1) {

dequeued = 0;

while(dequeued == 0) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&(ta->order_que->lock));

/*

* is the queue empty?

*/

if(ta->order_que->count == 0) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ta->order_que->lock));

/*

* if the queue is empty, are we done?

*/

if(*(ta->done) == 1) {

pthread_exit(NULL);

}

continue;

}

/*

* get the next order

*/

next = (ta->order_que->tail + 1) % ta->order_que->size;

order = ta->order_que->orders[next];

ta->order_que->tail = next;

ta->order_que->count -= 1;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ta->order_que->lock));

dequeued = 1;

}

/*

* have an order to process

*/

pthread_mutex_lock(&(ta->market->lock));

if(order->action == 1) { /* BUY */

ta->market->stocks[order->stock_id] -= order->quantity;

if(ta->market->stocks[order->stock_id] < 0) {

ta->market->stocks[order->stock_id] = 0;

}

} else {

ta->market->stocks[order->stock_id] += order->quantity;

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ta->market->lock));

if(ta->verbose == 1) {

now = CTimer();

printf("%10.0f trader: %d ",now,ta->id);

printf("fulfilled stock %d for %d\n",

order->stock_id,

order->quantity);

}

/*

* tell the client the order is done

*/

order->fulfilled = 1;

}

return(NULL);

}

In the trader thread there are three synchronization events (which I have tried

to boldface):

The trader includes an additional wrinkle for shutting down the entire simulation. In the case of the client, the main loop runs for as many orders as there are going to be for each client. The traders, however, don't know when the clients are done. To tell the traders, the trader argument structure

struct trader_arg

{

int id;

struct order_que *order_que;

struct market *market;

int *done;

int verbose;

};

includes a pointer to an integer (int *done) which will be set to

1 by the main thread once it has joined with all of the clients. That

is, the main thread will try and join with all clients (which will each finish

once their set of orders is processed), set the done flag, and then join with

all traders. Take a look at the main() function in the source code to see the details. However, in

the spin loop where the trader is waiting for the queue not to be empty, it

must also test to see if the main thread has signaled that the simulation is

done.

Note also that the traders must synchronize when accessing the market since each BUY or SELL order must be processed atomically. That is, there is a race condition with respect to updating the stock balance that the traders must avoid by accessing the market atomically.

Finally, once an order has been successfully executed, the trader sets the int fulfilled flag to tell the client that it can continue.

MossPiglet% ./market1 -c 1 -t 1 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 160194.266347 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market1 -c 1 -t 1 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 178848.307204 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market1 -c 1 -t 2 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 69281.818970 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market1 -c 1 -t 2 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 67015.364164 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market1 -c 2 -t 2 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 116164.790273 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market1 -c 2 -t 2 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 116390.389026 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market1 -c 100 -t 100 -q 100 -s 1 -o 10 425.016132 transactions / secStare at these results for a minute. Hilarious, no? What do they say, and then (more importantly) what do they mean?

First, on my Mac, the best performance is when there is 1 client, 1 trader, and a good sized queue between them to speed match. With 2 physical cores and only two threads you'd expect pretty good performance (especially if the i7 and OSX keeps the threads pinned to cores).

You can also see that hyperthreading isn't doing you much good. Intel says it gives you almost two additional "virtual cores" but when we run this code with 2 clients and 2 traders, the performance goes down by about a third. So much for virtual cores (at least under OSX -- try this on Linux and see if it is any better).

The size of the queue seems to matter sometimes, but not others (that's curious). And the performance is abysmal when there are 100 clients and 100 traders.

However, to see this effect, think of an extreme example where the time slice is 1 second. That is, when a thread is given the CPU, it will use it for 1 second unless it tries to do an I/O (print to the screen, etc.). Imagine that there is one processor (no hyperthreading), 1 client thread, and 1 trader thread. What is the maximum transaction rate? It should be about 0.5 transactions / second since in every second, there is a 50% chance that a client thread or trader thread is assigned the processor and during that second it simply spins waiting. Thus in half of the second, no work gets done while the CPU allows the spinning thread to run out its time slice.

It turns out that OSX (and Linux) is likely smarter than I've indicated in this simple thought experiment. Both of these systems "know" that the client and trader threads are calling pthread_mutex_lock() in their spin loops. The lock call generates a system call and there are really tricky locking features that can be employed. However in the client while loop where it waits for the int fulfilled flag and there is no lock, the OS has no choice but to let the thread spin out its time slice.

struct order_que

{

struct order **orders;

int size;

int head;

int tail;

int count;

pthread_mutex_t lock;

pthread_cond_t full;

pthread_cond_t empty;

};

in which two condition variables (for the full and empty conditions) have been

added. In the client thread, the queue synchronization becomes

while(queued == 0) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&(ca->order_que->lock));

/*

* is the queue full?

*/

while(ca->order_que->count == ca->order_que->size) {

pthread_cond_wait(&(ca->order_que->full),

&(ca->order_que->lock));

}

Notice how this works. Like before, the client must take a mutex lock.

However, the pthread_cond_wait() primitive allows the client to "sleep"

until it has been signaled and to automatically drop the lock just

before going to sleep. The client will sleep (not spinning on the CPU) until

some other thread calls pthread_cond_signal() on the same condition variable

that was specified as the first argument to pthread_cond_wait(). To

be able to drop the lock on behalf of the client, the call to

pthread_cond_wait() must also take (as its second argument) the address

of the lock to drop.

The pthread_cond_wait() primitive also has another important property. When the client is awoken by some call to pthread_cond_signal() it will be allowed to try and acquire the lock before the call to pthread_cond_wait() completes. Thus, when the wait is over, the client "wakes up" holding the lock.

pthread_mutex_lock(&lock);

while(queue->full == 1) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&lock);

/*

* whoops -- what if it goes to not full here?

*/

sleep();

pthread_mutex_lock(&lock);

}

There is a moment in time right between the call to

pthread_mutex_unlock() and sleep() where the queue status could

change from full to not full. However, the thread will have already decided

to go to sleep and, thus, will never wake up.

The pthread_cond_wait() call is specially coded to avoid this race condition.

Now take a look at the trader thread just after the thread has determined that there is work to do:

/* * get the next order */ next = (ta->order_que->tail + 1) % ta->order_que->size; order = ta->order_que->orders[next]; ta->order_que->tail = next; ta->order_que->count -= 1; pthread_cond_signal(&(ta->order_que->full)); pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ta->order_que->lock)); dequeued = 1;The trader thread must call pthread_cond_signal() on the same condition variable that the client threads are using to wait for the queue to no longer be full.

Similarly, the trader thread (before it processes an order) must ensure that there is work in the queue. That is, it cannot proceed until the queue is no longer empty. Its code is

dequeued = 0;

while(dequeued == 0) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&(ta->order_que->lock));

/*

* is the queue empty?

*/

while(ta->order_que->count == 0) {

/*

* if the queue is empty, are we done?

*/

if(*(ta->done) == 1) {

pthread_cond_signal(&(ta->order_que->empty));

pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ta->order_que->lock));

pthread_exit(NULL);

}

pthread_cond_wait(&(ta->order_que->empty),

&(ta->order_que->lock));

}

Here the trader thread is waiting while the queue is empty. Thus, the client

thread must signal a waiting trader (if there is one) once it has successfully

queued an order. In the client thread

ca->order_que->orders[next] = order; ca->order_que->head = next; ca->order_que->count += 1; queued = 1; pthread_cond_signal(&(ca->order_que->empty)); pthread_mutex_unlock(&(ca->order_que->lock));

The API for condition variables is

Thus, in this example, the calls to pthread_cond_signal() occur under the same lock that is being used to control the wait. That way, the signaler "knows" it is in the critical section and hence no other thread is in its critical section so there is no race condition that could cause a lost signal.

Another, more subtle point, is that a thread that has been signaled is not guaranteed to acquire the lock immediately. Notice that in the example, each thread retests the condition in a loop when it calls pthread_cond_wait(). That's because between the time it is signaled and the time it reacquires the lock, another thread might have "snuck in" grabbed the lock, changed the condition, and released the lock.

Most implementations try and give priority to a thread that has just awoken from a call to pthread_cond_wait() but that is for performance and not correctness reasons. To be completely safe, the threads must retest after a wait since the immediate lock acquisition is not strictly guaranteed by the specification.

Lastly, the specification does not say which thread (among more than one that are waiting on a condition variable) should be awakened. Again, good implementations try and choose threads to wake up in FIFO order as a default, but that isn't guaranteed (and may not be desirable in all situations). You should never count on the implementation of wait/signal in pthreads being "fair" to the threads that are waiting.

MossPiglet% ./market2 -c 1 -t 1 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 291456.104778 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market2 -c 1 -t 1 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 283434.731280 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market2 -c 1 -t 2 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 294681.020728 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market2 -c 1 -t 2 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 293809.091170 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market2 -c 2 -t 2 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 105729.484982 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market2 -c 2 -t 2 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 102448.573029 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market2 -c 100 -t 100 -q 100 -s 1 -o 10 369.965854 transactions / secYee haw! Not bad, eh? The best Solution 1 could do was about 178K transactions per second and Solution 2 goes like 295K transactions per second. Hyperthreading does even worse relative to non-hyperthreading in Solution 2, but it is still 40% faster than its Solution 1 counterpart. However, the test with a bunch of threads still really performs badly. Let's fix that.

First, we add a condition variable to struct order

struct order

{

int stock_id;

int quantity;

int action; /* buy or sell */

int fulfilled;

pthread_mutex_t lock;

pthread_cond_t finish;

};

Notice that we had to add a lock as well. Condition variables implement "test

under lock" which means we need to "test" the fulfilled condition under a lock

or there will be a race condition.

Next, in the client thread, we lock the order, test its condition (in case the trader thread has already fulfilled the order), and wait if it hasn't:

/*

* wait using condition variable until

* order is fulfilled

*/

pthread_mutex_lock(&order->lock);

while(order->fulfilled == 0) {

pthread_cond_wait(&order->finish,&order->lock);

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&order->lock);

Then, in the trader thread, instead of just setting the fulfilled flag

/* * tell the client the order is done */ pthread_mutex_lock(&order->lock); order->fulfilled = 1; pthread_cond_signal(&order->finish); pthread_mutex_unlock(&order->lock);Notice that the flag must be set inside a critical section observed by both the client and the trader threads. Otherwise, bad timing might allow the trader thread to sneak in, set the value, and send a signal that is lost in between the time the client tests the flag and calls pthread_cond_wait(). Think about this possibility for a minute. What happens if we remove the call to pthread_mutext_lock() and pthread_mutex_unlock() in the trader thread. Can you guarantee that the code won't deadlock?

MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 1 -t 1 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 156951.367687 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 1 -t 1 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 151438.489162 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 1 -t 2 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 150724.983497 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 1 -t 2 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 146666.960399 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 2 -t 2 -q 1 -s 1 -o 100000 91147.153955 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 2 -t 2 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 100000 90862.384876 transactions / sec MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 100 -t 100 -q 100 -s 1 -o 10 75545.821326 transactions / secUm -- yeah. For all but the last case with 200 total threads, the speed is slower. However, look at the last run. It is MUCH faster than the same runs for Solution 1 and Solution 2.

This exercise illustrates an important point in performance debugging. What might be fast at a small scale is really slow at a larger scale. Similarly, optimizations for the large scale may make things worse at a small scale. You have been warned.

In this case, however, the likely situation is that you have many more clients than traders. Let's see how they compare in that case.

MossPiglet% ./market3 -c 1000 -t 10 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 10 68965.526313 transactions / sec ./market2 -c 1000 -t 10 -q 10000 -s 1 -o 10That's right, market2 doesn't finish. In fact, it pretty much kills my laptop. I'm afraid to try market1. Seriously.

We'll leave the analysis of this code to you as an exercise that might prove both helpful and informative (especially as you prepare for the midterm and final in this class). Does it make the code even faster?

To see why condition variables in threads correspond to monitors, consider the way in which the client and trader threads syncronize in the examples.

A client thread, for example, tries to enter "the monitor" when it attempts to take the mutex lock. Either it is blocked (because some other client or trader thread is in the monitor) or it is allowed to proceed. If the queue is full, the client thread leaves the monitor but waits (on some kind of hidden queue maintained by pthreads) for the full condition to clear.

When a trader thread clears the full condition, it must be in the monitor (it has the queue locked) and it signals the condition variable. The pthreads implementation selects a thread from the hidden queue attached to that variable and allows it to try and re-enter the monitor by re-locking the lock.

Now, hopefully, it becomes clearer as to why the codes must retest once they have been awoken from a wait. Pthreads lets a thread that has been signaled try and retake the mutex lock that is passed to the wake call. For a monitor, this lock controls entry into the monitor and there may be other threads waiting on this lock to enter for the first time. If the lock protocol is FIFO, then one of these other threads may enter before the thread that has been awoken (it remains blocked). Eventually, though, it will be allowed to take the lock (it will get to the head of the lock's FIFO) but by that time, the condition may have changed.

This subtlety trips up many a pthreads programmer. Once you understand it in terms of a monitor with one shared mutex and several conditions that use the mutex, it makes more sense (at least to me).